G.K. Chesterton in his book

Orthodoxy: The Romance of Faith spoke of those men who had been thoroughly convinced of what they believed in--and contrasted them with those who were only nominally convinced of the same--thusly:

"It is very hard for a man to defend anything of which he is entirely convinced. It is comparatively easy when he is only partially convinced. He is partially convinced because he has found this or that proof of the thing, and he can expound it. But a man is not really convinced of a philosophic theory when he finds that something proves it. He is only really convinced when he finds that everything proves it. And the more converging reasons he finds pointing to this conviction, the more bewildered he is if asked suddenly to sum them up. Thus, if one asked an ordinary intelligent man, on the spur of the moment, 'Why do you prefer civilization to savagery?' he would look wildly round at object after object, and would only be able to answer vaguely, 'Why, there is that bookcase . . . and the coals in the coal-scuttle . . . and pianos . . . and policemen.' The whole case for civilization is that the case for it is complex."And so it is with Orthodoxy (big O) now that many paths, many inroads into my life have been made from various starting points (epistemology, aesthetics, work ethic, stewardship, sensory input, intellectual, emotional, and others). I believe that, were you to ask me "Why do you prefer Orthodoxy to Evangelicalism?" I would, in all honesty, have a hard time determining where to start my answer. Perhaps with the question, "How much time to you have?"

This was not the case in the beginning.

When I wrote the conversion story that's linked over in the sidebar, I wrote primarily about a group of particular theological issues that, due to a consensus concerning them in the Apostolic Fathers, I claimed as my basic reason for rejecting Protestantism and embracing Eastern Orthodoxy. If asked, I could (and would, and at the slightest provocation still do) prattle on about things like the early Church's treatment of the Eucharistic bread and wine as

nothing less and

nothing other than the Body and Blood of Christ Himself, made somehow mystically present in spite of the retention of the properties of bread and wine . . . the ability to trace one's bishop's ordination to one of the apostles as a hallmark of orthodoxy . . . salvation's being something that could be begun and thereafter lost . . . the practice of baptizing infants and seeing said moment as the moment wherein one is born again . . . Scripture's being by far the greatest influence on the Fathers' teachings yet not as a

sole rule of faith and thus accompanied by oral traditions which encompassed (mainly) issues of how to worship, etc . . . the divinization of man through theosis and Incarnational theology . . . and so on . . .

I think it's fair to say, then, that my initial conversion, while hinging on a very real paradigm shift regarding several key theological issues within the context of my faith, nevertheless reflected something of a shallow artificiality for a while -- I look at those days as one would a newly-bound branch that's still held on to a tree through inorganic, unnatural means, without which support the branch would simply fall off. I think I converted, at least in

part and

temporarily, because I felt I

had to based on theological arguments that had, to be honest, blindsided me. I was thus left in a limbo of sorts, wherein I had a place I knew I

couldn’t be, but no place I could call my soul’s home. I had not been

looking for or even

desiring Orthodoxy specifically, and--again, honestly--when first confronted with the vast experience thereof in worship, neither recognized it nor desired it at all, finally converting more out of obligation and commitment to intellectual honesty (which, I realize,

is admirable, albeit incomplete) than out of

real desire for Orthodoxy as the life of God, as the Kingdom of Heaven. I liken the subsequent years of feeling Orthodoxy as

the true life in Christ seep into me to that of a blind man receiving his sight all of a sudden, then being at a loss to describe what has been laid out before him, much less to be able to recognize the vision as beautiful and be thankful for it, blinking and squinting as he is for the first several moments.

Irenaeus said that the Faith is like a great mosaic of the King, and a heretic is not necessarily he who will take tiles from the mosaic and discard them; a heretic could be someone who simply takes all existing pieces and rearranges them into the image of a dog.

When a man converts to what he sees as original, apostolic Christianity, it behooves him not only to recognize that not only must he regard the image of a King rather than that of a dog, but he must also learn to prefer the King to the dog—-no, moreover, he must learn to

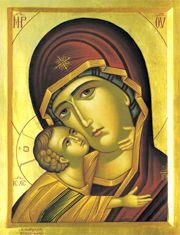

love the King through His proper image. I would dare say that this is the much more difficult step. It’s one thing for a man to embrace a faith because he’s aware that “the tiles just line up” in such and such a way; it’s another thing entirely to embrace said faith because he has stepped back, taken in the full image of the faith as newly presented icon, and been struck by the beauty of the scene. A man may convert out of obligation, out of commitment to correctness—-and anyone who converts to anything ought first to make sure he is regarding the proper image-—but there’s also a moment, or should be, wherein the man is taken in by a part other than his mind or his reason; said man has been caught by the Bridegroom Lover Whom he suddenly notices for the first time in this different way. Ask a man to tell you why he's in love; if he's really in love, he'll ask you how you could look at his beloved and

not be. We have moved from the mind of logic to the eyes and heart of desire, and this latter is what must complete the former.

It is one thing to affirm the doctrine of the Incarnation; it is another to listen to the prayers blessing a little one whose infancy has been blessed by the Creator’s infancy and, weeping, rejoice. It is one thing to acknowledge the uniform shape of liturgical worship in the first decades of Christianity; it is quite another to stand in Divine Liturgy and awaken to the notion that you are standing in the Court of the King, and that with you in that Court are Daniel, Isaiah, Ezekiel, and St. John the Theologian and Evangelist, writing down what they're seeing in that Eternal Now.

A prominent Evangelical theologian has stated recently (and, most likely, often before that) that there is

no uniform consensus in the fathers regarding

any doctrine whatsoever except for --

possibly -- monotheism, and thus we are free to parse apart the Scriptures and bring them together in whatever way we feel makes more sense. I cannot imagine the micromanaging of the Fathers that must occur for someone to come to such a conclusion, but all I can say to that is that I have been convinced otherwise, both by the fact that the pieces of the Christian Mosaic

do fit together in a way altogether foreign to the Reformers, and that the Church of the first few centuries agrees on and reveres the beauty within said arrangement.

As much as I might jerk back to a "what about...?" reaction regarding a particular verse or what not, I have to ask myself why a tree should feel itself worthy to overrule its overall context within its forest. Christ may tell us that we are

given to Him by the Father, but we are then told to

choose Him and

remain in Him. We are assured of our Father's love for us in Christ, yet we are warned against falling away from Him. We hear that God is not a man, nor is He like us, yet we hear of His rejoicing and His anger. As much as I might wonder about certain passages, what I've seen so far of the puzzle matches the front of the box, and that image, caressed by two thousand years of faithful lips, has taken me in. God grant I stay enthralled.

Why

Why all this talk of knowing and loving what or Whom one studies?

Why must we move from theological grocery lists to personal, breathing, penetrating Life? In essence, the latter allows us to bear witness as

person, instead of as a litany of

reasons. We thus

become our witness, we

embody that which God wills us to be, and thus provide "all things" within ourselves to all people through all the various facets of being a complete, Orthodox

person rather than just a well-read answerman operating solely on the level of the mind.